by Guest Historian Paul Haseman

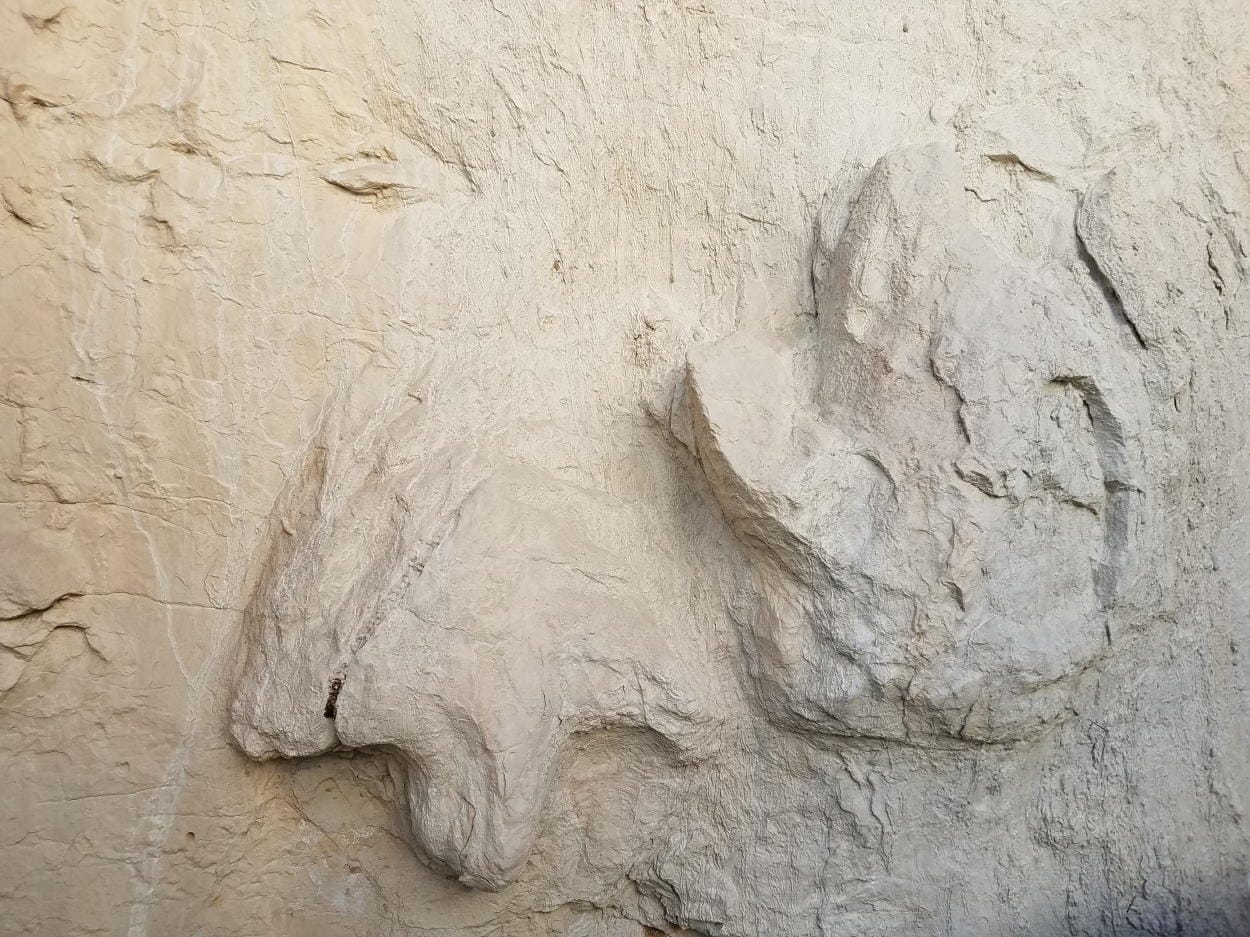

The good clay in Golden was early recognized, giving birth initially to a robust brick industry as early as 1864. This good clay from the nearby “claystone” became well known nationally and attracted not only brickmakers but also potential makers of fine pottery to include porcelain.

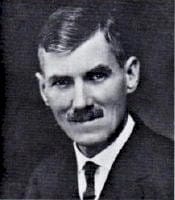

One person attracted to Golden was John Herold. Herold was a German emigrant who had been trained in the fine ceramic business in Germany. Coming to America he was a former art superintendent at the prestigious Roseville Pottery plant in Zanesville, OH. He spent some years in Ohio and then moved to Colorado in 1909 because of health reasons and needed Colorado’s drier air. Once here, he determined that local clay deposits fulfilled their growing reputation and promise for use in high temperature cookware and began experimenting with local clays.

For more than a year, Herold was a one-man operation until May 1910 , when he caught Adolph Coors’ attention after winning recognition at the Denver Keramic Club exhibition at the Brown Palace Hotel. Coors offered to go into business with Herold and offered Herold China a no-cost lease of a part of the former Coors Golden Glass Co. bottling plant located at 600 9th Street (map), which had been closed for 22 years following a union strike in 1888. The Colorado Transcript noted the following on 26 May 1910.

John J. Herold, who has been making extensive experiments with Golden clays, has secured the ground upon which the glass works formerly stood and will begin work at once upon a small factory for the manufacture of high class art goods. He expects to be in operation within six weeks. Mr. Herold was for many years superintendent of the art department and the entire plants of big potteries at Zanesville, Ohio. He does not intend to erect a large plant at first, but is confident that it will not be many years before his works will grow into a most extensive affair. Last week at the exhibit of the Denver Keramic club Mr. Herold was a special exhibitor, showing a number of pieces which he made here in Golden from local product, as well as a number of pieces which he created in the East. The result was that he received a number of orders for ware as well as an abundance of compliments and assurance of success.

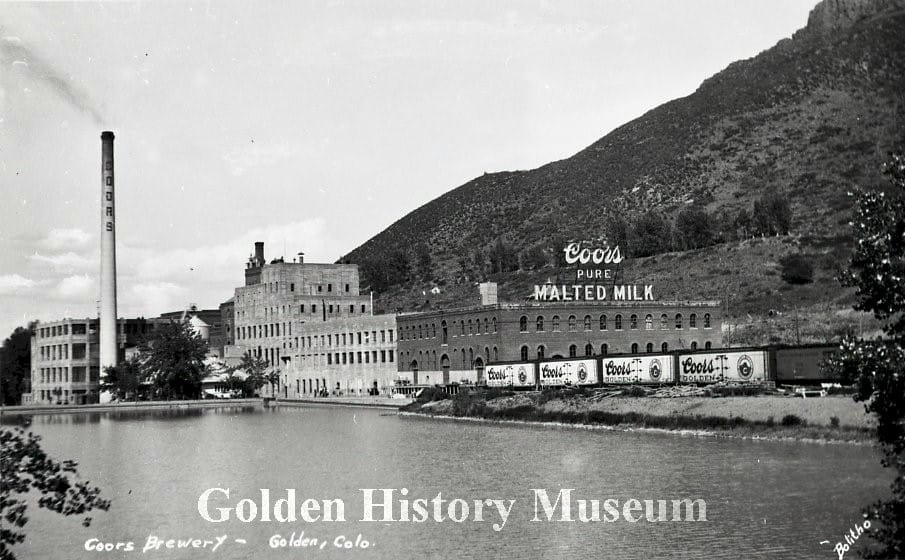

Catching Coors’ eye for quality and opportunity, Coors offered Herold the use of a portion of his defunct bottling plant at 610 9th Street and convinced other Golden businessmen such as Harry Rubey and Joseph Linder to invest in the Herold China and Pottery Co. But this was not magnanimity by Coors. As a good businessman, Coors saw a troubling future for beer brewing in Colorado. In 1907, a “Local Option” law was passed by the Legislature, leading several Colorado counties to go “dry.” And on 3 November 1914, the voters in Colorado enacted Statewide prohibition effective, 1 January 1916. With this “hand writing on the wall,” Coors early began diversification to include his entry into the ceramic business in 1910.

However, even with a new plant, the pottery did not do well with time dedicated to the hand painted novelties at which John Herold excelled. In any event, in 1912 Herold decided to give it up and join a Denver pottery business. Coors again stepped in and help raise additional capital, including his own funds and John Herold stayed on as manager. The plant was expanded and additional items were manufactured. However, with this investment by Coors he was elected President of the pottery on 6 Feb 1913 and his son, Adolph, Jr., Vice President. By 1914, with his normal style, Coors had bought out the other investors such as John Linder and Harry Rubey and owned Herold Pottery, which was run by his son, Adolph Coors, Jr.

Meanwhile, after initial success, a schism arose between Herold and Coors, perhaps over Herold’s business acumen or continued penchant for hand painted pottery. In any event, Herold and his family departed Golden in 1915 to return to Ohio, working at the Guernsey Pottery in Cambridge, OH, near Zanesville. That same year Coors successfully gained a preliminary injunction in Federal District Court to prevent Herold from disclosing Coors’s porcelain trade secrets to Guernsey Pottery. The injunction was later overturned, likely due to needed production for WWI.

Ah, yes, WWI. In literature, a plot device that unexpectedly “saves the day” is known as a deus ex machina and such an event was provided by Coors’ homeland, Germany, in the form of World War I. Prior to WWI scientific laboratories across the U.S. relied on German producers to meet their needs for high purity porcelain “chemical lab ware” such as crucibles, mortars and pestles. With the breakout of war in 1914, came an embargo on German goods. U.S. labs were forced to use inferior products then produced by American manufacturers which created serious issues with the quality and reliability of scientific results at a critical time in American history.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and perhaps the Government appealed to all American pottery manufacturers to develop the technology necessary to manufacture chemical porcelain ware to meet the demands of the Scientific Community. While 17 manufacturers responded to the call, only two, Herold China and Pottery and the Champion Sparkplug Company were able to meet the specifications.

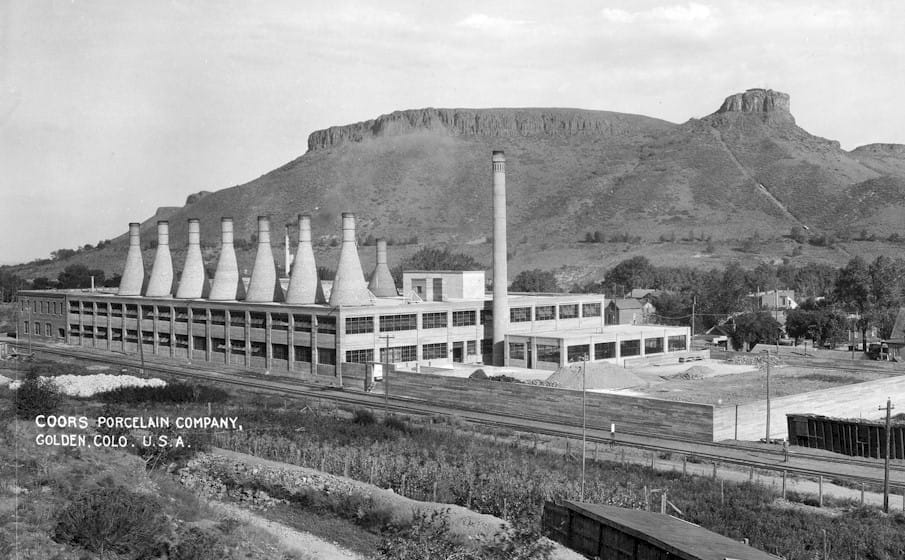

By 1916 Herold China and Pottery was supplying the needs of the U.S. scientific community and the company had grown significantly in size and revenue. As noted above, in that same year sale of alcoholic beverages was made illegal in Colorado and the Coors Brewery was forced to transform primarily into a supplier of malted milk and chemical lab ware. The success of the efforts in chemical porcelain manufacture were critical to the financial survival of the Coors business holdings during 16 years of Prohibition.

With the end of WWI the company began making high quality, durable service ware for hotels and restaurants. In 1922, the Federal Government again approached Coors to develop special products to support early research in atomic energy.

During the remaining years until the repeal of Prohibition, Coors ceramic and porcelain operations grew and was ever more critical to the financial health of the Coors businesses – especially during the depression years in the 1930’s. During WWII Coors Porcelain was a contributor of high purity ceramic technology critical to the success of the Manhattan Project – though at the time the project was so secret that the company had no idea where the products they made went or how they were used.

In its evolution of name changes, Herold China and Pottery became Coors Porcelain in 1920. Coors Porcelain became Coors Ceramics in 1986. In 2000, Coors Ceramics was renamed to CoorsTek, which flourishes today as a $1.3B leader in the technical ceramics business. And it all started with good Golden clay from the Golden’s geologic claystone beds in the Laramie and Dakota Formations tipped up by the rise of the Rockies on the west side of Golden.

Many thanks to Paul Haseman for researching and writing this article!