While I have enjoyed the dramatic lighting that accompanied the smoke from the wildfires, I hope this brief visit from winter will end the conflagrations. My neighbor took this photo on Sunday from Ulysses Park. The smoke filling Golden came from the Cameron Peak fire, which is about 70 miles away.

Public Health References

CDC * Colorado * Jefferson County * City of Golden

JCPHD normally updates the Coronavirus statistics Monday through Friday at about 3 PM. There was no update yesterday–probably due to the Labor Day holiday.

School of Mines COVID-19 case page.

Clear Creek is closed.

Masks are required.

City and County fire restrictions are in place.

Virtual Golden

10:15-11:15AM Baby & Toddler Time with the Library

1-2:30PM Zoom into Watercolor with Janet Nunn

6:30PM Friends of the Mines Museum Lecture

6:30PM Economic Development Commission Meeting – Virtual

The Economic Development Commission will be joined (virtually) by the head of the Jefferson County Economic Development Corporation. They will hear from city staff about the Good to be Golden program, the Jeffco Business Resource Center, efforts to encourage entrepreneurship and innovation, and business education and networking. They will also provide an update about Covid-19 programs. Finally, they will discuss their work plan for next year.

Real Life Golden

5-8PM VIBE@Five with the Golden Chamber at the Golden Hotel

Golden History Moment

WHITE ASH MINE DISASTER – 9 SEPTEMBER 1889

By Donna Anderson

This month marks the 131st anniversary of the worst mine disaster in Golden’s history: The White Ash Mine disaster.

Part 1. The White Ash and Old Loveland coal mines

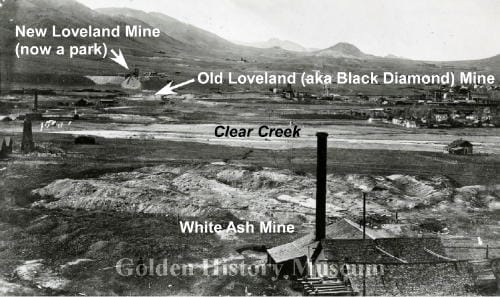

The White Ash coal mine was initially opened in 1874 by John Hodges and expanded in 1877 by R.D. Hall and A.L. Jones. It exploited a vertical coal seam, called the White Ash seam, so-called for its excellent burning properties that produced a clean, white ash. The mine portal was located at the west end of today’s 12th Street, and the vertical mine shaft and connecting horizontal tunnels were about 100 yards to the west.

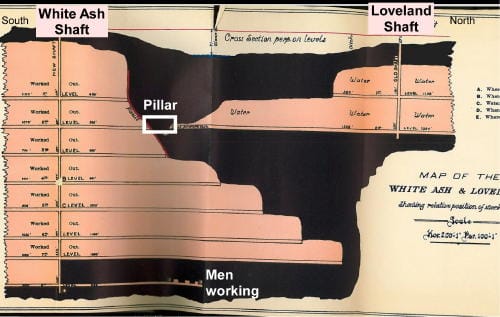

At its peak, the White Ash Mine produced 50 to 100 tons of coal per day and employed 40 miners working three shifts. Typical of the time, though, the mine was beset with problems. Mining paused in 1879 when a fire broke out at the 280-foot tunnel level. The tunnel was sealed up, with the hopes that a lack of oxygen would smother the fire. In 1885, the Golden Fuel Company entered into a 99-year lease with John Hodges and Charles Welch. From 1885 to 1889, the mine was deepened and had several accidents from falling rock and equipment, as well as bad air from carbon dioxide gas, and fires on the tailing piles. By 1888 the new owners had extended the mine to 720+ feet below ground, making it the deepest coal mine in the State at the time.

In 1889, State Coal Mine Inspector and engineer John McNeil visited the mine several times, finally requiring replacement of unstable timbers, as well as the drilling of a 700+ foot deep escape shaft at the north end of the mine, north of Clear Creek. He also restricted the number of miners to ten for any given shift for safety reasons. The mine owners replaced the rotten timbers and began to plan for an escape shaft in the summer of 1889. In a letter dated July 12, 1889, twelve miners petitioned the State of Colorado to keep the mine open due to hardship. Thus operations continued without the escape shaft.

Meanwhile, the “old” Loveland, aka Black Diamond, Mine was about 1960 feet north of the White Ash Mine, across Clear Creek and along the same coal seam as that of the White Ash Mine. The old Loveland Mine had been abandoned in 1879 due to suffocating inert gas, carbon dioxide or “black damp”, at its (lowest) 250-foot level. The abandoned Loveland shaft and tunnels were left to fill with water from seepage. In 1889, water from the flooded mine was being used as a water source for the steam boilers at the nearby Golden Brick Works, located downhill from the old Loveland Mine.

As it turns out, the lowest flooded tunnel in the Old Loveland Mine was near the exact same level as the 280-foot tunnel in the White Ash Mine, which had been sealed off in 1879 due to the earlier fire. A pillar of rock and coal 70-100 feet thick separated the two tunnels. This separation apparently caused some commentary in McNeil’s inspections, but he and everyone else considered the situation “safe enough.”

To Be Continued…..