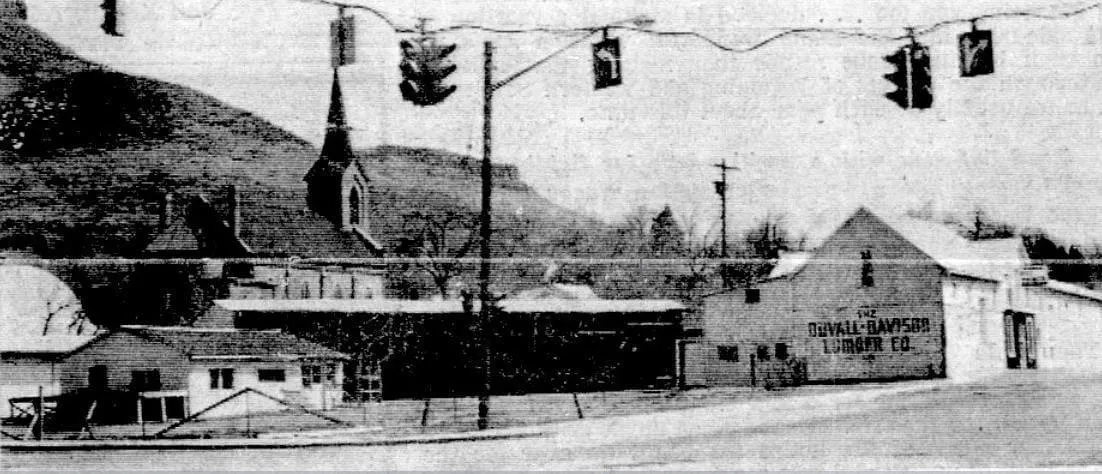

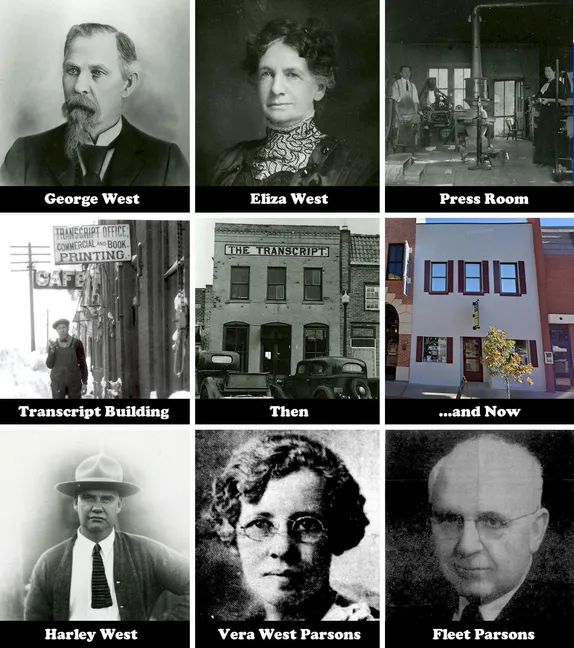

George Duvall ran a lumber business at 14th and Ford for more than 40 years. I occasionally search the Colorado Transcript for his name, both because he had an interesting life and because I live in his house!

Duvall was a Charter Member of the Golden Chamber of Commerce (in 1920), and immediately signed up to serve as the chairman of their Highways Committee. One of the Chamber’s very first projects was paving Golden’s dirt streets–a goal they pursued energetically for decades. Duvall had a bigger vision though–he wanted good roadways to connect Golden to other towns.

As the representative of the Golden Chamber, he worked with members of the State Highway Commission, and soon the Governor tapped him to join that group. His fellow commissioners named him to chair that committee. He represented our part of the state, and did a good job of it: he arranged to pave Morrison Road from Denver to Morrison, widened “the road by the Rock Rest” (now South Golden Road), and campaigned to build a highway from Golden to Boulder. He was constantly negotiating for improvements.

As I read those articles, I learned a thing or two about early roads. When Duvall started his work, roads were built without standards–they could be twisty, rutted, any width–whatever someone had built. Because earth-moving was so much more difficult and expensive in those days, roads generally went around natural barriers (like hills and mountains). As the state began to work with the Federal government, they had to learn to comply with an emerging set of standards.

By the 1930s, Mr. Duvall was serving as a Jefferson County Commissioner. There, too, he focused a lot of his attention on roads. He persuaded the state to designate 44th Avenue as a state highway, which came with some state funding. He continued to work on the Golden-Boulder highway.

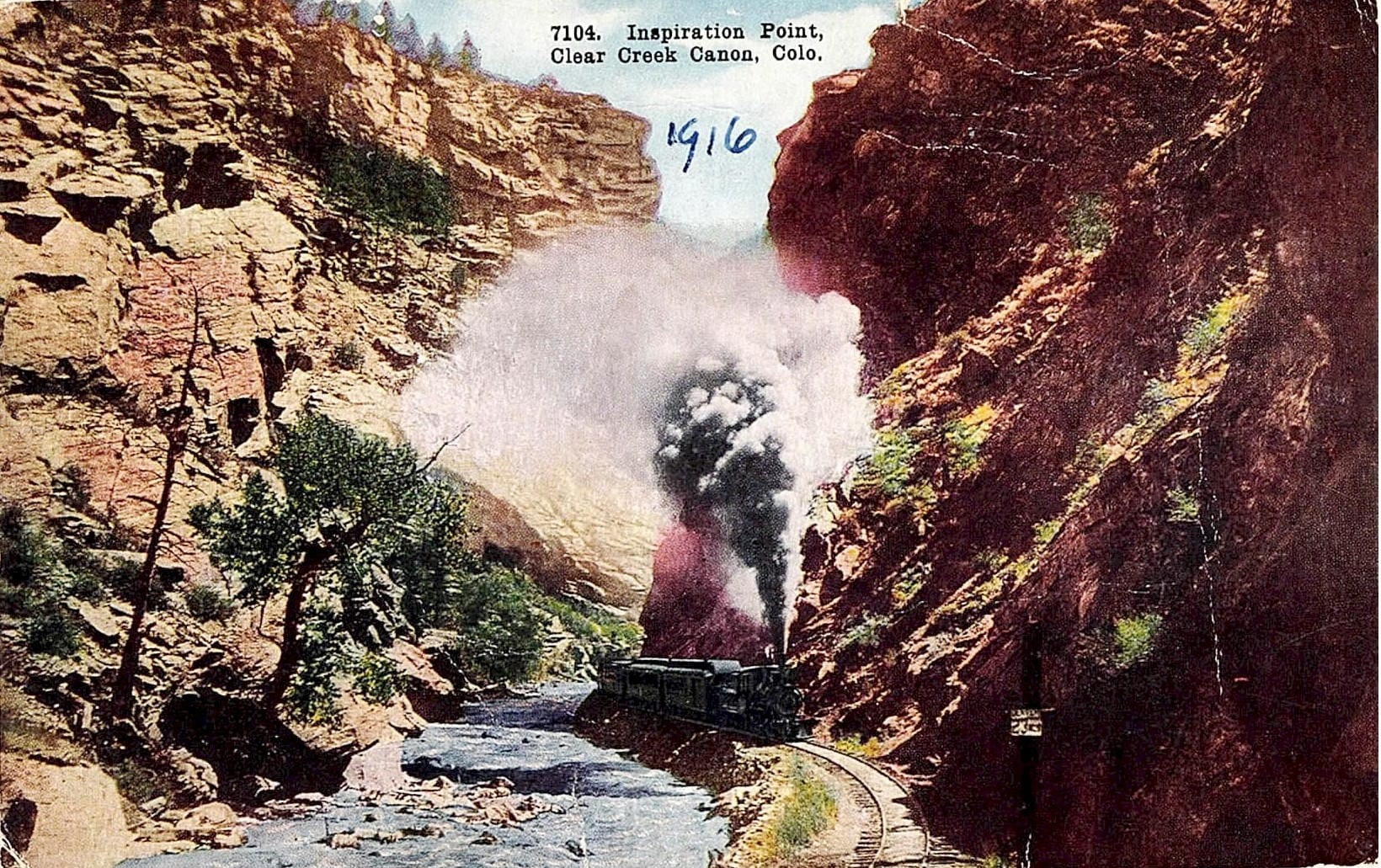

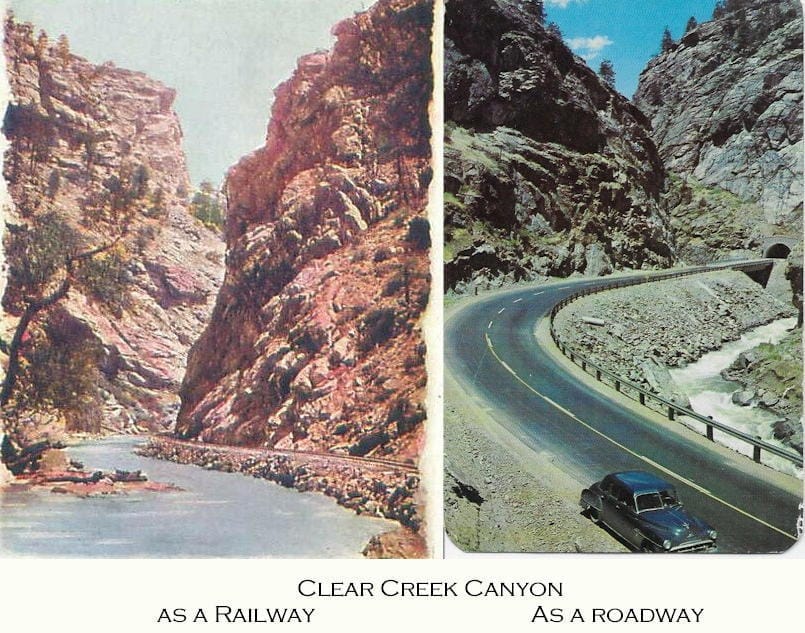

As early as 1928, he began working on his favorite, hardest, and longest lasting project: he wanted to build a highway through Clear Creek Canyon. Furthermore, he wanted it to be part of a coast-to-coast highway.

One complication was the Colorado & Southern Railway, which went through the canyon and used a lot of the right of way. The Railroad had no objection–the route lost money, and they wanted to abandon it. They required permission from federal regulators to do so, and the feds didn’t want to grant permission as long as the mountain towns still wanted rail service.

The State Highway Engineer (Charles Vail) was a bigger stumbling block. Vail didn’t want to build that road. He used various evasions over the years. First he said the project would cost $1.5 million, then when the State and the Feds came up with the money, he said it would cost $4 million–maybe $5 million.

When Roosevelt’s New Deal began, there were Federal grants available. To qualify, communities needed to build something worthwhile (like a highway) and they needed to employ local unemployed men. They agreed to fund a highway through Clear Creek Canyon.

Meanwhile, State Engineer Vail was funding any project but that one. He was particularly in favor of the Mount Vernon Highway (now I-70). That was a much more difficult path, since it went up and down mountains instead of running parallel to the Creek at the bottom of the canyon.

Finally Colorado started receiving threats from the Federal government, because we had accepted a grant to build in Clear Creek Canyon, but had not built the road. The Feds and Colorado’s Governor told Vail to start building the highway immediately. Vail said the grant money was gone–he had spent it on other projects.

One night, the Central City Opera House had a gala, and every influential person from this part of the state was there. Vail used the opportunity to announce that he was thinking of using the Clear Creek Canyon highway money to pave Highway 119. That road services Central City, so no doubt many of the opera-goers thought that was a great idea. Duvall responded that it was too late–the money was already tied up, budgeted and committed. The Transcript commented that they were surprised Vail hadn’t paved 119 while they were all inside, watching the opera.

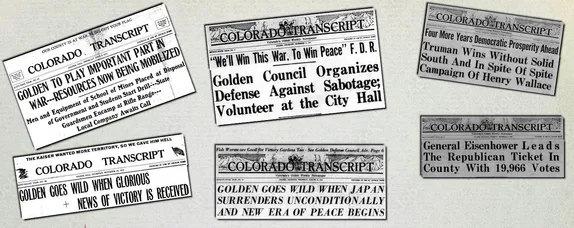

Finally, the fiances were worked out, and they were ready to start construction. The Transcript announced that the project was starting, and the Governor was all ready to wield a shovel for a groundbreaking ceremony. Then Word War II started! All money, men, and materials were diverted to the war effort for the next several years.

Charles Vail died in January, 1945 and the highway through Clear Creek Canyon was finally completed in about 1950.

Some newspapers wrote effusive obituaries in Vail’s honor. The Colorado Transcript did not:

HE KEPT HIS WORD

ENGINEER CHARLES D. VAIL died Monday at the age of 76. He said he would never in his life complete the Clear Creek Canyon road. He kept his word.

Colorado Transcript – January 11, 1945

George Duvall lived until March of 1964, so he was able to enjoy many years of driving on the roads he had helped build. He was 87 when he died, and had served his community for 55 years. He’s buried in the Golden Cemetery.

Many thanks to Esther Kettering for sponsoring Golden History Moments for the month of August.